I am 99% certain that a number of “large plants” in the Voynich manuscript have been consciously shaped to look like menorahs. This certainty is the result of accumulating insights, a number of consecutive finds by myself and others. I will present the pieces of the puzzle in chronological order, hoping you might understand why I feel this surpasses your average one-off resemblance.

But first… what exactly is a menorah? I did not know much about this subject, so here’s what I learned from some introductory research.

Two main types

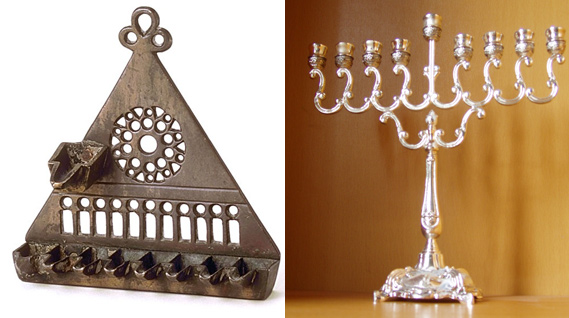

There are at least two main types of menorah: those with seven candles and those with nine. In modern society, the nine-candled type might be the most common one. It is also called a Hanukkah menora or hanukkiah. As the name suggests, it is exclusively associated with the festival of Hanukkah. Of both types, this one is much less ancient, as it did not exist yet during the first centuries CE.

The other, more original type is the “temple” menorah. Whether in a drawing or physical object, these always refer to the Biblical “lampstand made of pure gold and used in the portable sanctuary set up by Moses in the wilderness and later in the Temple in Jerusalem”. As such, it might be better to call them images of the menorah. Exodus 25:31–40 lists precise instructions on how God wanted the menorah to be constructed – but more on that later.

The Temple menorah is famously depicted on the 1stC CE arch of Titus (see above), in a scene showing the plundering of the Temple. It is on this image of the menorah that the modern symbol of Israel is based.

When you see a menorah in a medieval manuscript, it is most likely a depiction of the Temple menorah, which (unlike the hanukkiah) is mentioned in the Old Testament. Hence, it appears in Hebrew and Latin manuscripts alike.

Islamic tradition favored five-armed menorahs. And although clear instructions are present in the Bible, Latin copyists would regularly produce menorahs with strange shapes or an incorrect number of arms (which should always be seven).

1. Voynich menorahs – the first spark

In December 2017 I posted a very speculative thread to the Voynich Ninja forum titled “f22v – menorah?”, pointing out superficial resemblances between this plant and a branched candelabra (as commenters pointed out, the general candelabra might be a safer description than menorah specifically).

What set me onto the comparison was the image of a menorah found in a Roman catacomb. The lamps of the candelabra in this particular image don’t sit on the same line, which reinforced the resemblance with the plant.

Take note of the two lion heads at the very bottom, they will come back later. This is a standard funerary scene. Usually the roundel would contain a likeness of the deceased, but in this case the Jewish customer had chosen a menorah. The rest of the image is standard sarcophagus stuff – including the two lions as guardians of the tomb.

I also noted that the seemingly architectural base of the plant’s stem might be meant to bring to mind a lamp stand’s base, as in these examples:

And the following comparison with a menorah in the Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah (1296) reveals how in some cases the spaces between the lamp stand’s feet were even imagined as portals.

If we take the plant drawing and simplify it into what would be the candelabra’s shape, it becomes increasingly clear that there is a major difference with the vast majority of “proper” menorahs: the seven “lamps” are placed on four tiers instead of one or two.

Lamps on different tiers are found either in Christian candelabra (which still clearly reference the OT menorah) or in relatively crude Jewish imagery. It also looks like space constraints, as in the early Roman example above, could force the lamps out of line.

In both Hebrew and Latin examples it does happen that the central lamp is higher and/or larger.

Finally there is this example from a late 13th century Swiss Pentateuch, showing not a literal menorah but rather the harvesting of olives and making of oil for the Temple menorah. It is of note because it merges a candelabra shape with that of a tree, in a similar layout as the VM does.

2. More menorahs

A bit later, I noticed that the plant on the recto side of this very folio (f22) is also shaped like a candelabra. Its lower stem clearly brings to mind the squarish decoration often worked into a menorah’s base. Since this was during my Lauber period, it was a menorah in a 1430 Alsatian MS which first made this parallel apparent.

It does not require too much imagination to see how the plant’s base looks much more architectural than botanical, with the way the branches split and regrow. Furthermore, the red growths on top are arranged in the shape of a candelabra’s arms, and the blue fruits/flowers may reference a menorah’s cup-shaped oil lamps.

3. A third menorah folio

A recent blog post by Yulia May pointed towards yet another parallel between a Voynich plant and menorah imagery: f34v and the famous Rothschild Pentateuch. While her focus is on the alchemists’ tree of life, I would like to explore in greater depth the plant’s parallel with the actual menorah.

The crucial (and wonderfully clear) factor in Yulia’s linking of the images is the presence of a pair of animals sharing one head. In the Rothschild menorah, a pair of lions is placed beneath the base, while in the Voynich, the root is shaped like two animals, apparently merged at the head.

Now, animals sharing a head are not unheard of in all kinds of medieval imagery, but to see them in this context feels relevant. Are they purely for decoration, or is there a reason for their inclusion? It is certainly not an isolated case. Some examples, like the 1470 Kennicott Bible have one lion at the base. And beneath this menorah (1399, Italy) there are two lions looking away from each other. More common still are two (separate) lions flanking religious objects, like in below mosaic from Beth Alpha (6th century CE).

On the pairing of lions and menorahs, Rāḥēl Ḥa̱klîlî writes that lions seem to have been “persistently selected in their capacity as motifs of power or images of vigil to adorn synagogal and funerary art”. Lions are the symbol of Judah, the guardian and protector, and “lions flanking the menorah have the same significance”. Remember the Roman era sarcophagus I mentioned earlier in this post – it’s the same principle.

Apart from the Rothschild Pentateuch, there are these charming fellows from the probably related JTS MS Rab. 350. Both are from Germany/France and late 13th century. Since they are larger, the parallel with the VM plant becomes even more apparent.

You might have noticed the incredibly long and straight back of the VM animal on the left. It almost looks as if it is meant to reflect the shape of the candelabra’s base as well. Also notice the intentional asymmetry between both animals. Let’s zoom in:

In the Voynich there is a difference in size, while the Pentateuch uses a difference in color. In both cases, the tail is different. And finally, the leftmost animal in both manuscripts has a more marked coat than its counterpart on the right.

4. Almonds

If I understand correctly, Yulia May sees the alchemists’ “tree of life” motif as a link between menorahs and the appearance of the VM plant. While this may be true, my opinion is that we don’t need alchemical imagery (which is often later than the VM) but can stay closer to the menorah.

Let’s analyze the structure of the f34v plant. It’s got six side branches, three on each side. Three circles in the middle. One circle at the end of each branch. Three cicles hanging from most branches, but two branches have four circles.

The branches might bring to mind the six side branches of the menorah, although these are horizontal instead of bending upwards (as is the case in one of the other menorah-like plants). But the careful observer may have noticed that menorahs also tend to bear a series of round ornaments on their arms. Here’s a quick selection from 14th and 15th century manuscripts:

What are those? Why does every somewhat informed menorah image put knobs on the arms? Simple candelabra fashion? No, the answer is in the scripture, Exodus 25:

31 And thou shalt make a candlestick of pure gold: of beaten work shall the candlestick be made, even its base, and its shaft; its cups, its knops, and its flowers, shall be of one piece with it. 32 And there shall be six branches going out of the sides thereof: three branches of the candlestick out of the one side thereof, and three branches of the candle-stick out of the other side thereof; 33 three cups made like almond-blossoms in one branch, a knop and a flower; and three cups made like almond-blossoms in the other branch, a knop and a flower; so for the six branches going out of the candlestick. 34 And in the candlestick four cups made like almond-blossoms, the knops thereof, and the flowers thereof. And a knop under two branches of one piece with it, and a knop under two branches of one piece with it, and a knop under two branches of one piece with it, for the six branches going out of the candlestick. 36 Their knops and their branches shall be of one piece with it; the whole of it one beaten work of pure gold. 37 And thou shalt make the lamps thereof, seven; and they shall light the lamps thereof, to give light over against it.

In summary, the candlestick must be adorned with golden blossoms and knobs of almond trees. In practice, these threefold structures are often represented as one (sectioned) spherical decoration. Each arm must bear three of these almond-clusters (plus one lamp at the end), and there must be four on the central stem, for a total of 22. This plus seven lamps is 29 total items. There are 29 circles on the Voynich plant. Their arrangement is a bit puzzling, but their number is accurate – much more so than that of many medieval menorah images.

Next, let’s compare the fruits and flowers of the almond tree with the VM drawing.

I believe this plant might refer to the almond tree, and the resemblance with the menorah (which, by divine decree, is decorated with golden almond tree parts) is intentional.

Conclusion

It may be impossible to tell whether these plants refer to “the” menorah or rather more general candelabra. I have, however, attempted to demonstrate that at least f34v betrays familiarity with Exodus, and the description of the menorah therein. The fact that the menorah-like structure is found in not one, but at least three plants seems significant as well. Each of these three folios provided additional clues in the structure of the base.

I have attempted to limit my analysis mostly to comparing imagery, trying to avoid conclusions about possible cultural implications. Researchers like Diane O’Donovan have studied potential Jewish influences in the VM and know more about the matter than I do.

On the one hand, the horizontal branch structure (where the lamps don’t line up on top) is found more often in Latin works. But on the other hand, we have references here to one of the most important objects in Judaism, while generally religious symbolism in the VM is sparse. If my thoughts about the almond tree are true, then those references go deeper than a casual formal similarity.

Yes, I think it’s quite possible.

Some of the plants are so stylized, the possibility of menorah/candelabra references (or mnemonics) did cross my mind (many of the medieval scribes and translators were Jewish), but I wasn’t sure whether the imagery might be specifically referencing the menorah or perhaps to the Tree of Life (which includes menorah imagery).

Since I never had time to delve into it, I particularly enjoyed seeing your examples and comparisons because they do appear to add weight to the possibility that it was the menorah.

.

In case it might interest you, the region in which much of the “zodiac” imagery appears to have originated has significant overlap with a number of Jewish settlements that existed in Bavaria in the 12th to 13th centuries, including Lindau, Augsburg, Landsberg, Munich, Regensburg, Passau, Nuremberg, Bamberg, Würzburg, Randersacker, Schweinfurt, and Aschaufferburg. You may recognize the names of some of these, as they became major centers of scholarship and publishing in the 14th and 15th centuries (especially Regensburg and Augsburg) and tend to show up quite frequently in Voynich-related searches.

There were some major expulsions of Jews in the mid-14th century, leading up to the time of the VMS, but Regensburg was spared, and many of the Jews from other towns converged there, seeking refuge (in the mid 1400s, Jews were expelled from Augsburg as well, but this is probably after the VMS was created).

All of which is to say that there was a high degree of overlap between the Jewish communities and the major book-creation centers, some of whose publications are thematically consistent with the VMS zodiac figures (which means if it is menorah imagery, it would not be geographically out of step with what we know so far about exemplars for the zodiac section).

LikeLike

Interesting!!

LikeLike

Koen, thank you for this post, especially, for MS Rab. 350 fragment. The same question tortures me: can the shape of root of the f34v be just decorative or not? First of all, it doesn’t look too much decorative. Besides, all we observed those strongly pronounced details of masculine gender of the “animals”. Does it show just naughtiness of the author or he/she intentionally accented that those animals are male?

I still try to figure out this)

LikeLike

I don’t think that in the VM the shape can me merely decorative. At the very least, it appears to exploit a connection between confronting lions and the menorah/tree of life that apparently existed in its audience’s mind. Everything considered though, I must change my initial opinion about the lions. If the parallel you pointed out is relevant (which I think it is) and my research into the significance of lion-menorah pairing is to be trusted, then indeed the VM root-animals don’t tell us much about the plant. Their function would be to mimic familiar decorative symbols.

About the pronounced and naughty male members I am no longer certain either. I was convinced that the extra appendages absolutely had to be entwined penises (there’s a good one for “sentences that have never been used before”). However, if we take into account that the tree’s root may intend to bring to mind lion decorations at a menorah’s base, then the appendages may be part of that decoration. Either bas-de-page flourishing or part of the menorah’s stand. And again, less symbolically loaded than we may have thought.

But I’m not certain of that, I just think now that the possibility must be taken into account.

LikeLike

I think your strongest argument is the one where a menorah or candelabra combined with the animal forms at the base. It’s so hard to pin down the VMS, but when two kinds of imagery are together, sometimes it’s easier to gather and assess them for clues.

Some additional examples, some of which you might know about. These would go well with this group…

1) They’re not joined at the head, but the Regensburg Pentateuch (1300) has lions at the base of the menorah (the feet of the menorah are also lion paws):

http://cja.huji.ac.il/browser.php?mode=set&id=84

2) The Brandenburg Biblia has a single animal (probably a lion) with head inverted, with the stem of the menorah emerging from the mouth (folio 221r):

https://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/werkansicht?PPN=PPN689545150&PHYSID=PHYS_0001&DMDID=DMDLOG_0001

3) The Speculum humanae salvationis is interesting because it has “smiley” lions without claws uder the base. One of the distinctive characteristics of the VMS is that most of the figures seem quite friendly and benign, even the almost-fierce ones seem friendly compared to those in other manuscripts. These critters are not arranged like conjoined animals, they face out in five directions, but they have a VMS-like friendly feel to them (folio 23v):

http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=add_ms_11575_fs001r

4) For the stilt-like group (without animals), this is in a Polish Hebrew manuscript, folio 71r (unfortunately, not a good one, the base goes off the bottom of the folio). SOme of the ancient mosaics also had the “stilt” style:

http://www.manuscriptorium.com/apps/index.php?direct=record&pid=AIPDIG-BUW___F_47087_5___0XH245E-cs#search

.

And this might be of interest for contrast (in terms of geolocation). Look how strikingly different this design is (Spain, c. 13th century):

http://www.sothebys.com/fr/auctions/ecatalogue/lot.234.html/2011/arts-of-the-islamic-world

Those in Catalan manuscripts are more recognizable:

https://britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk/.a/6a00d8341c464853ef019b0222513e970d-500wi

.

Interestingly, these Hanukkah lamps (Or 5024, Bologna, 1374) are topped with Ghibelline merlons instead of the more usual columns-motif. I’ve always assumed the Ghibelline merlons on the VMS “map” folio were intended as landmarks, but maybe not:

https://britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk/.a/6a00d8341c464853ef019b0221d6f5970b-500wi

CLM 146 has a menorah drawing with flower-like joints.

Vad Slg 352 has two lion feet.

Every once in a while, candelabra have hooves but the connection to lions and menorah seems more compelling to me than hoofed animals and candelabra.

.

Sorry, this ran longer than I intended (and I didn’t even include all the links), but I started researching this some time ago and wasn’t able to finish, so it seems best to pass it on where it might be useful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Luckily there’s a few sites with a wealth of medieval menorah images, it makes this job much easier 🙂

On the one hand (as I intended to demonstrate) there’s a historical and natural connection between “guardian lions” and holy objects like the menorah. Their presence is far from obligatory, but definitely an option.

In addition to that though, there’s the particular motif of the conjoined-head lions at the base of the menorah, linking our image to two possibly related manuscripts: the Rothschild Pentateuch and Rab 350.

They appear to have been made around the same time in the same area (France, possibly finished in Germany). Hence, one would expect one menorah composition to have influenced the other, but I haven’t found enough information about Rab 350 yet.

LikeLike

Koen, thanks for the mention. JTS MS Rab. 350 is an excellent find; well done.

LikeLike

Koen,

I’ve been thinking about why someone would might associate the idea idea with each of the three types of plant.

Some possibilities: that the plants are named by a word which recalls the idea; or that they yield an oil considered sufficiently pure (presumably only in regions where olives didn’t grow); or that their wood was acceptable for making the candlesticks.

The difficulty is knowing enough about practices in earlier times and/or in regions at a distance from the holy land. (This issue proved very difficult to research when, in connection with a different botanical folio, the question of substitutes for the etrog came up).

Just looking online now, I find that the candlestick may be made of wood, although it would take time, and advice, to know which woods were/are acceptable in each time and region.

In India, brass never too expensive, and it was used, but elsewhere…?

Opinions about acceptably pure oil varied too; strictly it must be olive oil but obviously not feasible everywhere even now, let alone in the earlier medieval centuries.

About the ‘entwined appendages’ – that has to do with the plant being pictured -the detail is a mnemonic, not an icon.

Religio-cultural associations make the mnemonic’s association easier to recall and habitually inform them, regardless of which culture or religion we’re speaking about – but that doesn’t turn the image into a religious icon; just reminds the viewer of whatever-it-was.

It could be as simple as a reminder that the plant (its fruit, wood, oil etc.) is ripe at the time of the annual festival; or perhaps that candlesticks carved of this wood have been proven popular with the Jewish market, or something of that kind.

Traditionally -and I’m not speaking particularly of the Jewish context – two lions signify ‘sunrise and sunset’ as birth and death; beginning and end; day and night; the primordial pair.

The custom of showing two creatures with a single conjoined head began in Persia and entered the Mediterranean even before Alexander’s day; it was never popular in Europe though does occur in some vernacular art of the crusader period (e.g. the sort of wood-carving seen on pews). Showing the bodies of distinctly different sex or species is quite rare in European works – the earliest example I found in Jewish art was 8thC Karaite. To show distinctly different sex/species but with an apparent aversion to depicting the face is something I’ve not seen anywhere in any form of art so far from the Mediterranean-and-adjacent-regions.

Which reminds me, Koen, that find of yours makes a lovely three-point line. From 8thC Syria through Cairo to Iberia and then 13thC France/Germany. One finds the introduction and dissemination of micrography (in the proper sense, not Newbold’s) follows a parallel path. Hope not T.M.I.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Koen,

this was really interesting!

I want to add something, which I hadn’t realized until I saw your illustration of 22v with what you call “portals” outlined in black.

They may be portals or arches; as you note, there are many examples of these at the base of menorahs.

However, there is another option: that they show the outline of the covenant aka the tables of law, the two stone tablets bearing the ten commandments.

This would explain the weird hatched motif on one side of the “arches”, to render the thickness of the tablets.

These are almost always depicted with rounded tops.

They are also frequently found at the base of menorahs. But so far I have not found such menorahs for the medieval period, only later ones.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ha, that’s certainly an option! My thinking of them as portals kind of blocked that interpretation, but you may be right. There’s a genre of menorah illustration where they are pictured together with implements, and also stone tables on the opposite page.

Here’s a great example: http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=49316

Also, if you click the image, you see that on the menorah there are hooked attachments. And on VM f22r there’s also an unusual hooked attachment.

LikeLike

Before, and during, the time period of the VM there were frequent expulsions or forced conversions of European Jews. Might the VM — or certain parts of it — be an aide-memoire for Jews? A reference work, allowing them to preserve and pass on their traditional observances and cultural practices? (cf. Women bathing: mikveh, niddah?)

LikeLike

Hi Lisboeta

I think it’s possible that Jews’ (forced) migration had something to do with the images we see in the manuscript. I just don’t believe that “Jews” by themselves are enough to explain everything.

The mikvah theory has been suggested before, but what bothers me is that there exists zero evidence that Jews or Jewish women would be comfortable with depicting themselves in this way. Throughout much of Jewish art history, there was even a hesitation against human images full stop. Let alone wrestling naked female figures.

Additionally, I believe the naked figures in the water have more in common with Classical imagery:

LikeLike

Hi, Koen. After reading your analysis, I wondered the reason why we can’t see any other Jewish element. I mean, why was the author going to include, for example, a menorah disguised as a plant but we can’t see a six-pointed star , the hamsa hand or the mezuzah? Thanks.

LikeLike

Hi Carmen, that’s a good question.

There are two things to consider. One, there is very little overt religious imagery in the manuscript. It is very, very, very unusual to get ca. 300 human figures in a medieval work, yet so few of them with a clear connection to any faith. One might hypothesise that the makers had no reason for bringing more religious imagery into this kind of work, or perhaps they wanted to avoid censorship. But that’s all speculation.

A second point is that the presence of candle sticks, whether menorah or otherwise, needn’t necessarily imply that the makers were Jewish. Christians were also familiar with the old testament, and perhaps more importantly, anyone could have visually referred to a menorah or candlestick without therefore bringing a religious message.

Imagine that the form of the plant implies “you can make lamp oil from this plant” for example. Then the hidden image of the candelabra might be practical and to the point rather than a secret expression of religious identity.

LikeLike

I cannot but agree with you. However, I don’t think that censorship is mere speculation. You have used a key concept. That is, we only hide what we do not want to be discovered. The reasons behind may vary from person to person but basically the fear is there. And all this reminds me of the Papal Decretal in 1317 (Spondet Pariter by Pope John XXII) and how many alchemists were persecuted. Similarly, the Jews also underwent an institutionalised discrimination here in Spain for years until their expulsion in 1492.

About the candlestick , you mention that “the hidden image of the candelabra might be practical”. But how could we consider practical an unreadable text or its instructions? If we cannot read the MS, how could we know the candelabra-plant means exactly that?

I know you are using just an example to illustrate a verbal-visual parallelism. So here the study of its visual semantics in context would be an interesting field to be explored. Of course, without cognitive biases such as pareidolia, apophenia or the gorilla effect/inattentional blindness we all have had somehow while studying the MS.

Thanks and sorry for expanding on this.

LikeLike

Oh no reason to be sorry, this subject is quite interesting and certainly an important part of understanding VM imagery.

You are right, if the makers of the MS were Jewish they would certainly have had reasons to avoid the censor. This remains a possibility.

What I mean though is that I have a hard time seeing the hidden menorah/candelabra as a secret profession of faith. If this were the case then, as your initial question suggests, we would see more of these things throughout the MS.

By “practical” I mean of course practical to the original maker or his audience. Maybe the image of the candelabra relates to the name of the plant, or one of its uses, or a story, or some other piece of knowledge they wanted to tie to this plant.

We, on the other hand, won’t have certainty until the text is understood. But that the hidden images are there, of that I am fairly sure. There is too much going on to set this aside as pareidolia, and in some cases they aren’t hidden at all (like the faces in the roots).

You are right that there is still plenty of room for study here, and that we might learn a lot. But how to do this while avoiding all those common pitfalls, I don’t know. The study of VM imagery is so often seen as a subjective affair – just see the comments to my most recent post about the “armadillo” as an example…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks , Koen.

By the way, about the armadillo dilemma… If real, the animal could be even a mammal from the big family Mustelidae (a badger, an ermin, a marten,

a ferret among others). These mammals represented an abstract concept (purity, independence, nobility) but the problem, as I see, is that there is a nymph holding a ring below it. So both drawings may be (or not) connected in some way. Enfin…

LikeLike